-

“Out of control” fuel subsidies seen as hampering economic growth

-

Top Indonesian presidential candidates want to reduce fuel subsidies

-

Fuel-related industries likely to suffer; infrastructure projects may benefit

-

Minor protests can be expected as a result of subsidy cut

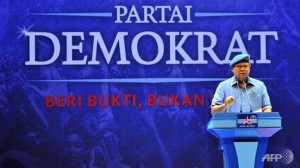

On July 9th, Indonesians will go to the voting booth to elect their next president. Two frontrunners have emerged: Joko Widodo, the current governor of Jakarta, and Prabowo Subianto, a businessman with ties to the Suharto regime. Widowo is widely favored to win, but his victory is far from certain. The only certainty is that the new leader will inherit Indonesia’s complex fiscal environment and will need to deal with the country’s increasingly urgent fuel subsidy crisis.

Understanding Indonesia’s economic climate

In the last decade, President Yudhoyono has taken Indonesia through a boom period, growing at an average of 5.8% per year over the last 10 years. With a GDP of US$878 billion in 2012, it is now the world’s 16th largest economy, ranking above the Netherlands.

However, Indonesia’s economic growth has slowed in recent years. A depreciating currency and an increase in its current account deficit have contributed to the slowdown. In 2014 Q1, the economy only grew 5.2%, the smallest growth it has seen in the last 4 years.

President Yudhoyono expects the deficit to increase, recently adjusting his budget deficit forecast for 2014 to an estimated 2.5% of GDP. This is much higher than the original forecast of 1.69% and higher than its 2013 budget deficit of 2.38%. This forecast is also notable for being within striking distance of Indonesia’s legally mandated threshold for its GDP deficit, set at 3%. Fuel subsidies are one of the chief reasons for the newly inflated forecast.

Economic impact of the fuel subsidy

Indonesia’s fuel subsidies create a situation where the price of fuel is dramatically lower than what consumers would normally pay. This leads to consumer overuse of resources, leading to waste and an increasing financial burden on the government. This is evidenced by the following table, illustrating the country’s soaring fuel subsidy budget from 2010-2013. In practical terms, this translates into a subsidy of 35% for every liter of gasoline bought.

Indonesian Fuel Subsidies 2010-2013

Instead of producing its own oil, Indonesia is now at the mercy of international oil prices. Indonesia has been a net importer of oil since 2004. With its weakening currency, Indonesia has had to spend much more to get the same amount of fuel: every 100 IDR (US$0.00842) weakening of the currency results in an additional 3 trillion IDR (US$254 million) worth of spending on fuel subsidies. It’s an acknowledged problem, and observers are hoping that incoming leadership have promising ideas on how to solve it.

Presidential candidates’ stances on subsidies

For the upcoming presidential election, Widodo and Subianto have both made controlling the country’s soaring fuel subsidies one of their key campaign issues. For Widodo, this means a slow reduction of fuel subsidies over a period of 4-5 years. Subianto’s proposal involves policies that hold fuel prices steady, but only for poor and lower middle-class income citizens.

There is agreement among election front-runners, politicians, and the Indonesian media that fuel subsidies have to be decreased. But what impact might this have on Indonesia?

Analysis: Political Risks

The biggest impact that a fuel subsidy cut will have on Indonesia is its political stability. Fuel subsidies is a legacy of the country’s original founding father, Sukarno. Under him, and every succeeding leader of Indonesia, fuel subsidies have been implemented to soften the blow of high inflationary prices for the country’s lower income citizens.

Looking to historical precedents suggest caution: it was a combination of fuel subsidy cuts, inflation, and high food prices that led to Jakarta’s city-wide riots that overthrew President Suharto in 1998. President Wahid (1999-2001) and President Megawati (2001-2004) also faced protests and dissent before each subsidy cut.

The exception is President Yudhoyono (2004-present), who conducted campaigns to mentally prepare the population before the roll out of his fuel subsidy cut. He also gave handouts to lower income citizens to hedge against any dissent.

With Indonesia’s growth and increased economic power in the last decade, it is unlikely that a fuel subsidy reduction will trigger a repeat of the 1998 events. Furthermore, each subsequent protest has been focused solely on towards government policy, where the 1998 Jakarta riots were also focused on inflicting violence towards companies and businesses.

Analysis: Industry Risks & Opportunities

The industries most negatively impacted by a fuel subsidy cut will be downstream fuel companies and sectors involved in automobile, transportation, or shipping in Indonesia. With an estimated 1 million new cars and 8 million new motorcycles hitting the streets each year, this number may dramatically decrease once fuel prices normalize to market equilibrium. Expect families to begin carpooling to reduce fuel costs or to move their families closer to offices and schools. The money saved from cutting subsidies may also be invested in public transportation infrastructure.

Favorable changes are likely to occur in the energy sector. Due to artificially cheap fuel prices, Indonesia has not had the right environment in which to encourage renewable energy or fossil fuel exploration. Investment in these areas will surely increase like it has for other countries in the Asia-Pacific region. This offers a chance for both domestic and foreign firms to invest in Indonesia’s energy future.

Outlook

As Indonesians head to the polls, they’re seemingly being asked to vote against their own best interests. The front-runners are two candidates who have openly pledged to make their daily lives more expensive. Both tout fuel subsidy policies that will harm Indonesia’s automobile, transportation, downstream fuel, and shipping sectors- established industries that employ many Indonesians.

While cutting fuel subsidies may cause some minor political and social unrest, there is wide agreement that it will secure the international competitiveness of Indonesia in the years to come. In 2013, fuel subsidies took 19.5% of the total government budget, amounting to 2.1% of the GDP. This amount can be put toward much needed infrastructure, education, and healthcare; international businesses and organizations dealing in these sectors should be watching closely.

Presidential front-runners Widowo and Subianto view their fuel subsidy reforms as a critical part to putting Indonesia back on the road to growth, and they’re hoping Indonesians see it the same way.